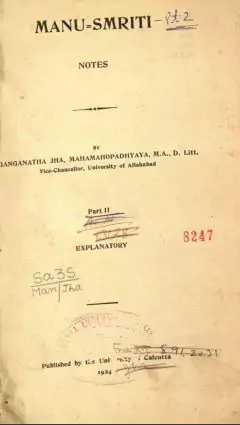

‘The Laws of Manu Notes’ PDF Quick download link is given at the bottom of this article. You can see the PDF demo, size of the PDF, page numbers, and direct download Free PDF of ‘Manu Smriti Notes PDF’ using the download button.

Notes of Manusmriti Book PDF Free Download

Manusmriti Notes PDF For Students

The Manusmriti, or ‘The Laws of Manu’, is considered to be one of the most authoritative texts in the Brahminical tradition which lays out social and civil laws and codes of conduct that are necessary for the maintenance of dharma.

It prescribes the conduct for men and women of the four social classes or varnas – Brahman, Kshatriya, Vaishya, Shudra – and rules of interaction between them.

In addition, it lays out rules of conduct for people in the four stages of life, ashramas – brahmacharya, grihstashrama, vanaprastha, and sannyasa.

It also prescribes rules and obligations for the King – rajdharma – and laws related to civil matters like business and contract.

The purpose of these rigid social rules and boundaries is to preserve dharma – the social order marked by a hierarchical varna system, where the Brahman enjoys the most social privileges and Shudra the least.

The proper sphere of activity for the Brahmin is the study of the Vedas and begging, for Kshatriya is statecraft, for Vaisya, it is trade and moneylending, and for Shudra is to serve the above three.

The Shudras are not entitled to an education. All four varnas enjoy complete control over the women of their social category.

Thus the ‘Laws of Manu’ do not contain a distinction between secular and religious laws. It is the social law that dominates the political as well as the personal sphere.

Even the kingly functions are aimed towards the preservation of the social order. Historians do not consider ‘Manu’ to be one historical person.

Rather, what we know as the ‘Laws of Manu’ is the handiwork of several Brahmin individuals, which was compiled in the early centuries of the Common Era in Northern India.

Manu appears to be a mythological figure in Brahminical tradition and later in the Hindu religion, who has often been called the first human being.

The 2694 stanzas divided into twelve chapters of Manusmriti talk about a range of issues: caste restrictions, dietary restrictions, restrictions on women, rites of marriage, death and sacrificial ceremonies, purification rituals, penalties for breaking these rules and rules of polity to be followed by kings.

The social laws of Manu offer us a glimpse into how the powerful sections of early India, the Brahmins who composed the work, desired the society to be.

A study of Manu’s social laws will also provide a glimpse of how society was sought to be organized because the ideas contained in the book were not entirely new, but the culmination of the Brahminical tradition of social thought which traced itself to the Vedas.

Such detailed and elaborate rules of social control were made to avoid chaos, or what Vedic texts have called Matsyanyaya, an anarchic situation where only the law of the stronger exists.

Thus, Manusmriti appears to be an attempt by socially powerful sections of Indian society to retain and preserve the social order of their privilege, at a time when rapid historical changes were taking place.

The Manusmriti forms part of the smriti canon of the Hindu religious corpus, which refers to knowledge received from tradition. The other canon is shruti which refers to revealed knowledge or divine knowledge.

The Vedas belong to the shruti group and occupy a somewhat superior position.

The classification of religious knowledge between shruti and smriti, ultimately indicates two sources of law – the divine and traditional.

Although, repositories of traditional knowledge claim that revealed texts are their source.

The Laws of Manu claim four sources of sacred law; the Vedas, the conduct of virtuous men learned in the Vedas, the conduct of holy men, and self-satisfaction.

It also claims that all the social laws prescribed in it are in strict accordance with the Vedas. Tracing the origin of law to the divine is a way to command obedience, and to claim that the law stands above human scrutiny.

Such a source also enables the dominant social sections of society to claim that they are eternally entitled to respect, wealth, and political power.

Because divinely ordained laws are unchanging and depend on the conduct of those already in power, they seek to bolster their position privileged position.

For instance, historian K.P. Jayaswal explained that the divine origin theory of kingship was furthered by Brahmin king Pusyamitra Sunga in order to make his family’s claim to the throne permanent and to discredit the Buddhist theory of the state which emphasized contract amongst people to decide their ruler.

Why was the king created?

The king was created to protect and control chaos and fear which prevailed in a society without a ruler.

A Kshatriya who has received training in Vedic tradition and has gone through all the prescribed religious practices from childhood – the initiation (upanayana) and studentship – is fit to be king, according to Manu.

A king is superior to all other living beings because he is made out of divine elements from the gods.

Manu demands total obedience to the laws of the King. It is the king who preserves and protects the social order of the four varnas, the dharma.

Hence, disobedience of the king is akin to sacrilege and invites the severest reprisal.

The instrument employed by the king to preserve and protect the social order is danda or punishment. Echoing Arthashastra, the Manusmriti claims that punishment is the king itself.

It is a punishment that watches over, governs, and which protects. Manu warns that danda has to be applied after due consideration in order to lead toward happiness.

Recklessly applied punishment destroys everything. If danda is not employed, then ‘the stronger would roast the weaker, like fish on a pit,’ ‘the crow would eat the sacrificial cake and the dog would lick the sacrificial viands, and ownership would not remain with anyone, and the lower ones (would usurp the place of) the higher ones.’

These metaphors explain that the social order, where wealth, property ownership, education, and religious training are reserved for the three higher varnas, would crumble.

‘All castes (varnas) would be corrupted (by intermixture), and all barriers will be broken through.’

Manu fears that in the absence of punishment, the endogamous rules of marriage within the same caste, or between the male of a higher caste and female of a lower caste, would be broken and caste hierarchy and entitlement over power and resources would lose all meaning.

An ideal king, therefore, has to be truthful to the social order and should observe justice and dharma by making sure that the social and economic restrictions placed by the varna order are not broken.

A king who is of unsound mind, who is addicted to sensual pleasures, and who is partial and deceitful will not be able to govern or adhere strictly to the caste order.

Manu, therefore, spells out that ‘The King has been created to be the protector of the castes and orders, who, all according to their rank, discharge their several duties.’

A just King has to ensure that the castes do not break ranks – do not intermarry and do not take up occupations that are not prescribed for them.

In addition, in dispensing justice, the King ought to ‘with rigor chastise his enemies, behave without duplicity towards his friends, and be lenient towards the Brahmanas.’

The King should always remember his role as the protector of the social order. For this purpose, ‘Let the king, after rising early in the morning, worship the Brahmins who are well versed in the three-fold sacred science and learned in (polity), and follow their advice.’

To strictly protect the caste order, the King should not only worship learned and aged Brahmins but should also cultivate virtue and shun vice.

Only a king who has mastered self-control and is free of envy, wrath, and resentment will be able to ensure that each caste follows its stipulated occupation and does not come with others socially through marriage.

The only relaxation to this strict system of social rules could at times be made for the Brahmin.

The king should shun all sorts of vices like excessive love for hunting, gambling, the company of women, singing music, and dancing because they can lead him astray from ruling and cloud his judgment according to Manusmriti.

Women for Manu are similar to property and other objects of desire, who should be possessed, but their ‘use’ should be controlled. This shall be elaborated upon in the section on Social Laws for women.

Thus, Manu not only invokes the divine theory of kingship, but he also extols danda as the instrument of raj dharma.

It is through punitive violence that things are kept in their place. To carry out the everyday administration of the state, the Manusmriti offers a great deal of detailed practical advice to the King regarding the appointment of ministers, foreign relations, the conduct of war, the system of spies, and other juridical and civil functions.

Manu advises that the King should employ seven or eight ministers from families who have served him well, who belong to noble (upper castes) families, who are trained in the use of weapons, and whose worth has been proven.

The king should daily consult with them on matters of war, peace, administration of towns and kingdoms, treasury and revenue, defense, and tributes.

Tasks that are difficult for the King alone become far easier with the aid of trusted assistants.

The most important issues should be discussed with the most trusted and distinguished Brahmin among his ministers.

Security from external enemies from outside is as important as the maintenance of social order within the kingdom.

The Laws of Manu advise the King to have skillful and knowledgeable ambassadors for the conduct of diplomacy.

The ambassador enables the king to have allies – they negotiate peace or war.

The king should rely on ambassadors to inform him beforehand of the enemies’ designs.

The defense should be the uppermost concern of a Kshatriya king and by employing the four expedients – conciliation, bribery, dissension, and force – the king should protect his kingdom.

As Arthashastra, Manusmriti advocates that against a powerful enemy, conciliation should be tried first, followed by bribery and discussion.

If all else fails, only then coercion should be adopted. Yet, the king ought to be prepared for any eventuality and is advised to build forts at convenient locations in towns and hills, well stocked with soldiers and weapons.

| Author | – |

| Language | English |

| No. of Pages | 847 |

| PDF Size | 53 MB |

| Category | Religious |

| Source/Credits | ignca.gov.in |

Related PDFs

Manusmriti Notes PDF Free Download