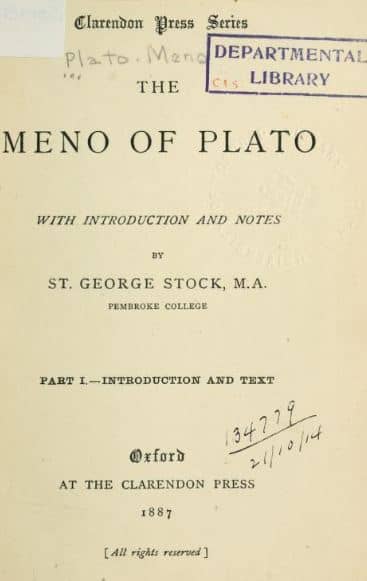

‘Meno’ PDF Quick download link is given at the bottom of this article. You can see the PDF demo, size of the PDF, page numbers, and direct download Free PDF of ‘Meno’ using the download button.

Plato Meno Book PDF Free Download

ON THE IDEAS OF PLATO.

Plato’s doctrine of ideas has attained an imaginary clearness and definiteness which is not to be found in his own writings.

The popular account of them is partly derived from one or two passages in his Dialogues interpreted without regard to their poetical environment.

It is due also to the misunderstanding of him by the Aristotelian school, and the erroneous notion has been further narrowed and has become fixed by the realism of the schoolmen.

This popular view of the Platonic ideas may be summed up in some such formula as the following: ‘Truth consists not in particulars, but in universals, which have a place in the mind of God, or in some far-off heaven.

These were revealed to men in a former state of existence, and are recovered by reminiscence (anamnesis) or association from sensible things. The sensible things are not realities, but shadows only, in relation to the truth.’

These unmeaning propositions are hardly suspected to be a caricature of a great theory of knowledge, which Plato in various ways and under many figures of speech is seeking to unfold.

Poetry has been converted into dogma, and it is not remarked that the Platonic ideas are to be found only in about a third of Plato’s writings and are not confined to him. The forms which they assume are numerous, and if taken literally, inconsistent with one another.

At one time we are in the clouds of mythology, at another among the abstractions of mathematics or metaphysics; we pass imperceptibly from one to the other. Reason and fancy are mingled in the same passage.

The ideas are sometimes described as many, coextensive with the universals of sense and also with the first principles of ethics; or again they are absorbed into the single idea of good, and subordinated to it.

They are not more certain than facts, but they are equally certain (Phaedo). They are both personal and impersonal. They are abstract terms: they are also the causes of things, and they are even transformed into the demons or spirits by whose help God made the world.

And the idea of good (Republic) may without violence be converted into the Supreme Being, who ‘because He was good’ created all things (Tim.).

It would be a mistake to try and reconcile these differing modes of thought. They are not to be regarded seriously as having a distinct meaning.

They are parables, prophecies, myths, symbols, revelations, and aspirations after an unknown world. They derive their origin from a deeply religious and contemplative feeling, and also from observation of curious mental phenomena.

They gather up the elements of the previous philosophies, which they put together in a new form. Their great diversity shows the tentative character of early endeavors to think.

They have not yet settled down into a single system. Plato uses them, though he also criticizes them; he acknowledges that both he and others are always talking about them, especially about the Idea of Good; and that they are not peculiar to himself (Phaedo; Republic; Soph.).

But in his later writings, he seems to have laid aside their old forms of them. As he proceeds he makes for himself new modes of expression more akin to the Aristotelian logic.

Yet amid all these varieties and incongruities, there is a common meaning or spirit that pervades his writings, both those in which he treats the ideas and those in which he is silent about them.

This is the spirit of idealism, which in the history of philosophy has had many names and taken many forms, and has in a measure influenced those who seemed to be most averse to it.

It has often been charged with inconsistency and fancifulness, and yet has had an elevating effect on human nature, and has exercised a wonderful charm and interest over a few spirits who have been lost in the thought of it.

It has been banished again and again but has always returned. It has attempted to leave the earth and soar heavenwards but soon has found that only in experience could any solid foundation of knowledge be laid.

It has degenerated into pantheism but has again emerged. No other knowledge has given an equal stimulus to the mind. It is the science of sciences, which are also ideas, and under either aspect required to be defined.

They can only be thought of in due proportion when conceived about one another. They are the glasses through which the kingdoms of science are seen but at a distance.

All the greatest minds, except when living in an age of reaction against them, have unconsciously fallen under their power.

The account of the Platonic ideas in the Meno is the simplest and clearest, and we shall best illustrate their nature by giving this first and then comparing how they are described elsewhere, e.g.

in the Phaedrus, Phaedo, Republic; to which may be added the criticism of them in the Parmenides, the personal form which is attributed to them in the Timaeus, the logical character which they assume in the Sophist and Philebus, and the allusion to them in the Laws.

In the Cratylus, they dawn upon him with the freshness of a newly discovered thought.

The Meno goes back to a former state of existence, in which men did and suffered good and evil, and received the reward or punishment of them until their sin was purged away and they were allowed to return to earth.

This is a tradition of the olden times, to which priests and poets bear witness. The souls of men returning to earth bring back a latent memory of ideas, which were known to them in a former state.

The recollection is awakened into life and consciousness by the sight of the things that resemble them on earth. The soul possesses such innate ideas before she has had time to acquire them.

This is proved by an experiment tried on one of Meno’s slaves, from whom Socrates elicits truths of arithmetic and geometry, which he had never learned in this world. He must therefore have brought them with him from another.

| Author | Plato |

| Language | English |

| No. of Pages | 136 |

| PDF Size | 5.9 MB |

| Category | Novel |

| Source/ Credits | archive.org |

Related PDFs

The Republic PDF By Plato In English

No Longer Human PDF By Osamu Dazai PDF

The Delectable Negro PDF By Vincent Woodard

Jerry of the Islands PDF By Jack London

If It’s Not Forever It’s Not Love PDF

Meno Book PDF Free Download